How it all began

After I moved to Riga with my family in 1999, a Latvian journalist asked me if during my 48 years in the United States, I hadn’t sometimes thought of my self as an American. Although I was born in Munich, Germany, I moved to the US at the age of 2. I spent 33 years in Chicago and the next 15 in Washington, D.C. Between 1968 and 1991, I was even a naturalized U.S. citizen.

But no, I never felt like an American. I couldn’t. Why? Because my name was Ojārs Kalniņš. The first time I uttered this name to a real American, most likely around 1955 in the Nash Grammar school kindergarten class on the West Side of Chicago, the utter incomprehension on my classmate’s face made it clear to me I wasn’t one of him.

I soon discovered that I wasn’t just ‘not American’. I wasn’t really anything that anyone had ever heard of. My parents told me I was Latvian because they had come to Chicago from a country called Latvia. I knew that the language we spoke at home was something called Latvian. But here in the real world, in school, on the street, or in our neighbor’s kitchen, being from Latvia was like being from the Land of Oz. Except that Oz was well known, while Latvia was not. We weren’t even a fairy tale.

Thus, from early childhood I found that I had to explain myself. I had to explain Latvia. I had to explain where on earth this country could be found, what kind of people lived there and what kind crazy language it was that we were speaking. In grammar school I had to convince other kids I wasn’t making it all up. (No, Latvia was not an ally of Groucho’s Fredonia.) In high school, I had to convince them that Latvia really did exist in some form, despite the fact that it was buried (as Krushchev had promised the US) in the Soviet Union. And in college I had to explain why it all really mattered.

Actually, in college I wondered why anything mattered. I was studying philosophy and that’s what philosophy majors did. We wondered. And doubted everything. It was at this stage that Latvia achieved a sense of equality in my mind with the rest of the world, because if nothing really mattered, then Latvia was as important (or unimportant) as anything else. I felt a sense of existential empowerment.

Somewhere at the end of my college days, between Nietzsche, Kierkegaard and Sartre, I reached the conclusion that my philosophy of life was best captured in the one comic book I had consumed with a passion during my early childhood Mad Magazine. Suddenly, all the silliness, idiocy and oddness of Mad made sense. As befits an ambitious college student, however, I soon moved on to reading the National Lampoon, which replaced Mad as my private window to the world behind the veil. I not only devoured the National Lampoon, I idolized it, studied it and tried to emulate it.

By the time I left college and got a job as a copywriter in the advertising business, I had mastered the cynically satirical thought processes that were necessary to write ad copy about industrial sump pumps. When I developed ideas for a client, I imagined I was writing for Mad or the National Lampoon, and then simply toned it down with some subtleties tailored for the customer.

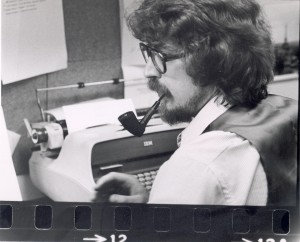

It was around this time, in 1978 that I first set foot on the soil of the near legendary Latvia that I had been explaining so often to so many people. When I returned to the United States I decided to use my writing skills to explain Latvia to Americans in a new way. I created a cut-and-paste newsletter (this was way before blogs) called the Latvian International Press Service (L.I.P.S.) and started sending it (by snail mail) to editors, journalists, radio stations, TV news anchors and anyone else who I felt should know something about Latvia. It was a satirical newsletter in the spirit of the National Lampoon and touched upon many topics of current interest, but in each issue I also included something about Latvia. In the conviction that humor has a longer-lasting effect on the human psyche than dead seriousness, I distributed L.I.P.S. under the motto: “When the truth isn’t enough.”

L.I.P.S. did garner some interest from other irreverent-minded editors, and in 1981 even landed me a brief gig as Ojārs the Latvian’ on the morning show of Chicago’s progressive rock station WXRT. I wrote skits for the morning DJ Gary Lee Wright and sometimes even appeared on the air.

But I also continued to explain Latvia in more serious ways and started writing letters-to-the-editor to every US magazine and newspaper, always seeking ways to infiltrate some information about Soviet-occupied Latvia into the text. Many of my letters were published and I eventually became the editor of the Chicago Latvian Newsletter, a monthly 4-page flyer published by the local Latvian community. In 1985 I was offered a job as a lobbyist for the American Latvian Association in Washington, D.C. My mission of explaining Latvia now extended to the halls of the U.S. Congress, State Department and White House.

To make a long story short, in January 1991 I joined Latvia’s diplomatic mission in exile, the Latvian Legation, as their public affairs liaison. When Latvian restored its independence later that year, the Legation became the Latvian Embassy, and I became Deputy Chief of Mission. I was also assigned to our newly established Mission to the UN in New York, and that same year I found myself on the podium of the U.N. General Assembly, explaining Latvia one more time to this august body of international diplomats.

I ended up serving as Latvia’s Ambassador to the United States from 1993 until 2000, and for the next 10 years I served as the Director of the Latvian Institute, a state agency whose mission is to explain Latvia. In 2010 I was elected to the Parliament of Latvia, where I became what I am now, namely the Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee and head of Latvia’s delegation to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly. And wouldn’t you know it, I am defending, representing and explaining Latvia once again, this time from a parliamentary perspective. Life has improved immeasurably, because everyone in the EU and NATO has not only heard of Latvia, but has a pretty good idea where it is located. Even Paul Krugman has heard of Latvia, probably more often than he likes.

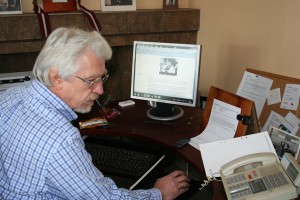

Now that the days of cut-and-paste have been replaced by bits and bytes, I figured it may be worth someone’s while to assemble everything I have written over the years and collect it here for posterity. This may take time, because a great deal of my earlier writings are rapidly fading on yellowing photocopies and will need to be ‘re-entered’ in digital form. As I find them, I will bring them in.

Even though much of the earlier material is dated and out of context for young, 21st century readers, it may have some historical value to those who like to dig around in the past.

And perhaps, just perhaps, it will explain a little more about the country I love.

***

If you’ve gotten this far and still care, a brief guide to what’s in here:

COMMENTARIES – recent thoughts, since leaving the LI.

LATVIAN INSTITUTE – stuff about Latvia that I’ve written as Director since 2000.

HISTORY – my various takes on Latvian history.

LV90 BLOGS – blogs written for Latvia’s 90th anniversary.

ODD ENDS – what I do to amuse myself.

L.I.P.S. – something from my presumptuous youth.

LYRICS/POEMS – distracting ditties